Kafka vs. RabbitMQ #1

August 10, 2022

As dealing with microservice-based systems, we often encounter the ever-repeating question , “Should I use RabbitMQ or Kafka?” For some reason, many developers view these technologies as interchangeable. While this is true for some cases, there are various underlying differences between these platforms.

As a result, different scenarios require a different solution, and choosing the wrong one might severely impact your ability to design, develop, and maintain your software solution.

The goal of this piece is first to introduce the basic asynchronous messaging patterns. Then, it continues to present both RabbitMQ and Kafka](https://kafka.apache.org/) and their internal structures and highlights the critical differences between these platforms, their various advantages and disadvantages, and how to choose between the two.

Asynchronous Messaging Patterns #

Asynchronous messaging is a messaging scheme where message production by a producer is decoupled from its processing by a consumer. When dealing with messaging systems, we typically identify two main messaging pattern — message queuing and publish/subscribe.

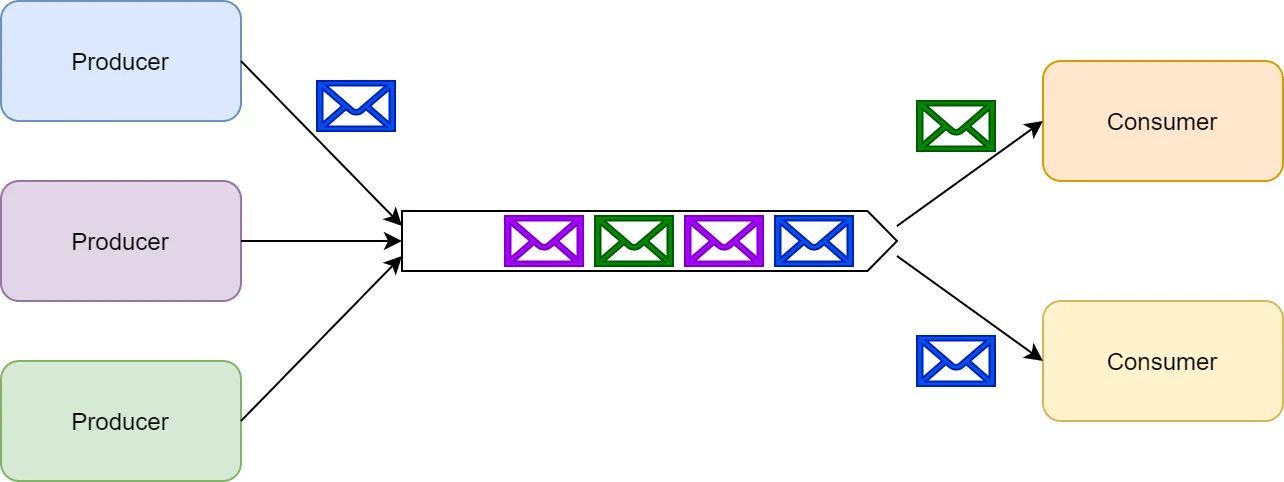

Message queueing #

In the message-queuing communication pattern, queues temporally decouple producers from consumers. Multiple producers can send messages to the same queue; however, when a consumer processes a message, it’s locked or removed from the queue and is no longer available. Only a single consumer consumes a specific message.

As a side note, if the consumer fails to process a certain message, the messaging platform typically returns the message to the queue where it’s made available for other consumers. Besides temporal decoupling, queues allow us to scale producers and consumers independently as well as providing a degree of fault-tolerance against processing errors.

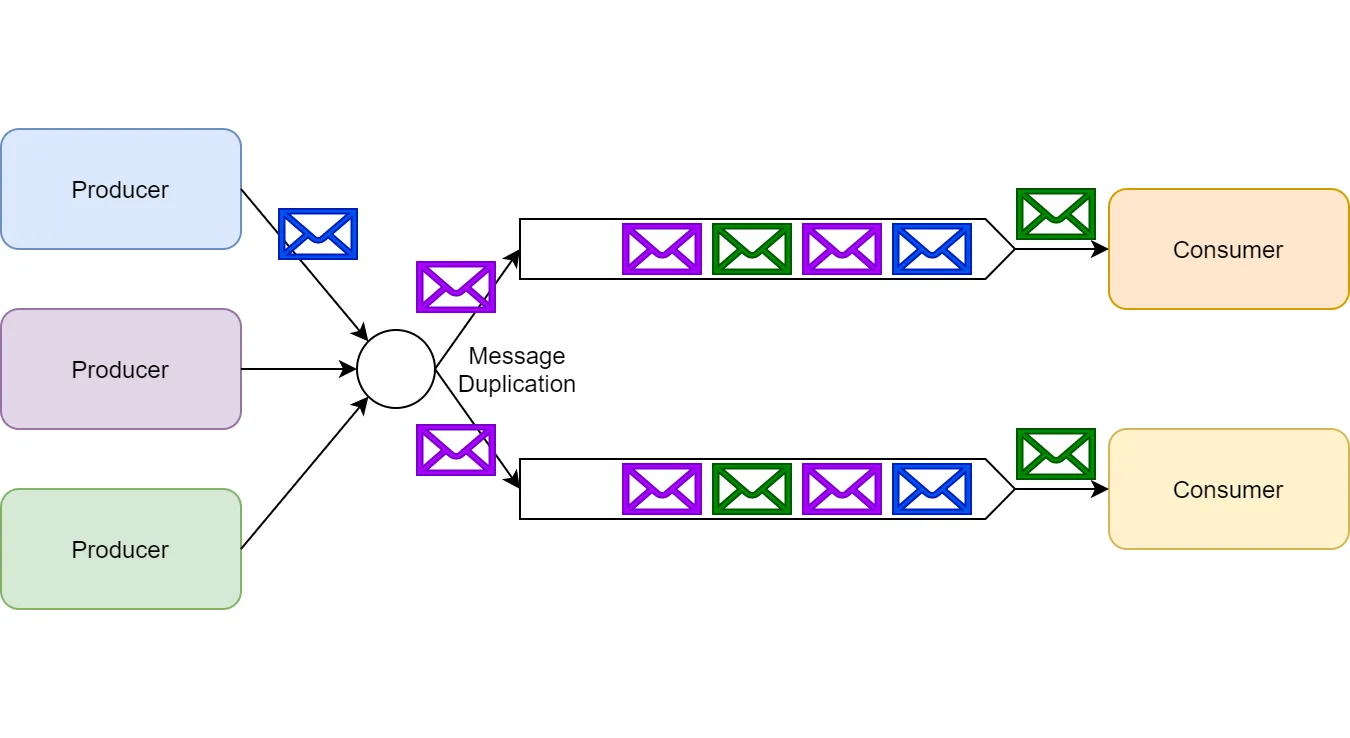

Publish/subscribe #

In the publish/subscribe (or pub/sub) communication pattern, a single message can be received and processed by multiple subscribers concurrently.

This pattern allows a publisher, for example, to notify all subscribers that something has happened in the system. Many queuing platforms often associate pub/sub with the term topics. In RabbitMQ, topics are a specific type of pub/sub implementation (a type of exchange to be exact), but for this piece, I refer to topics as a representation of pub/sub as a whol

Generically speaking, there are two types of subscriptions:

- An ephemeral subscription, where the subscription is only active as long the consumer is up and running. Once the consumer shuts down, their subscription and yet-to-be processed messages are lost.

- A durable subscription, where the subscription is maintained as long as it’s not explicitly deleted. When the consumer shuts down, the messaging platform maintains the subscription, and message processing can be resumed later.

RabbitMQ #

RabbitMQ is an implementation of a message broker — often referred to as a service bus. It natively supports both messaging patterns described above. Other popular implementations of message brokers include ActiveMQ, ZeroMQ, Azure Service Bus, and Amazon Simple Queue Service (SQS). All of these implementations have a lot in common; many concepts described in this piece apply to most of them.

Queues #

RabbitMQ supports classic message queuing out of the box. A developer defines named queues, and then publishers can send messages to that named queue. Consumers, in turn, use the same queue to retrieve messages to process them.

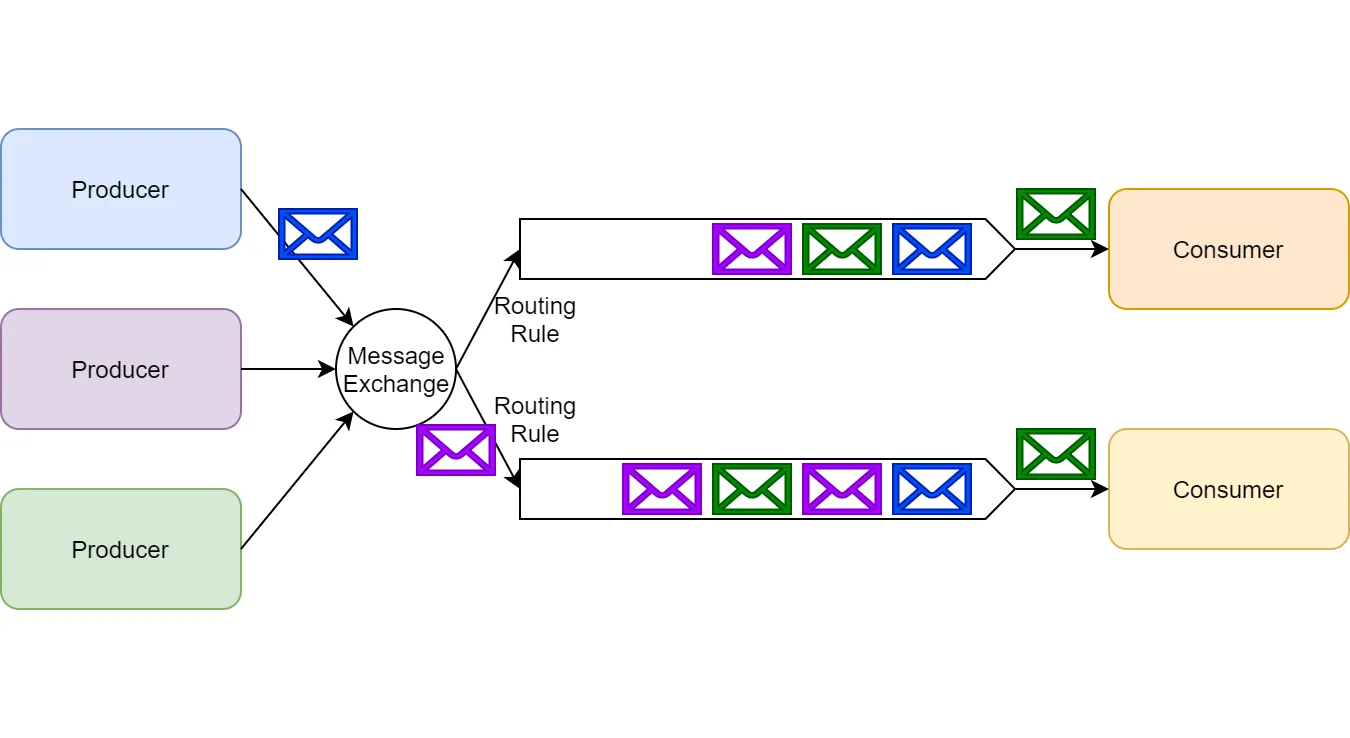

Message exchanges #

RabbitMQ implements pub/sub via the use of message exchanges. A publisher publishes its messages to a message exchange without knowing who the subscribers of these messages are.

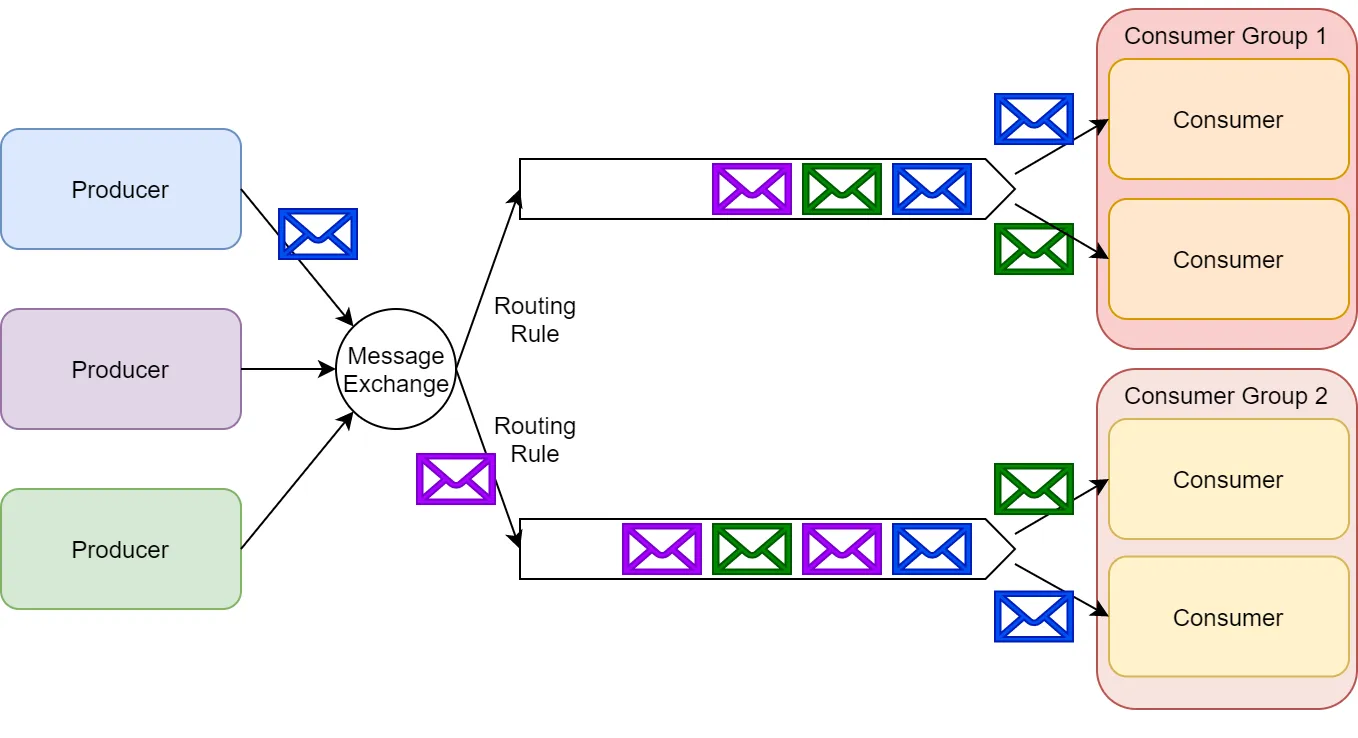

Each consumer wishing to subscribe to an exchange creates a queue; the message exchange then queues produced messages for consumers to consume. It can also filter messages for some subscribers based on various routing rules.

It’s important to note RabbitMQ supports both ephemeral and durable subscriptions. A consumer can decide the type of subscription they’d like to employ via RabbitMQ’s API.

Due to RabbitMQ’s architecture, we can also create a hybrid approach — where some subscribers form consumer groups that work together processing messages in the form of competing consumers over a specific queue. In this manner, we implement the pub/sub pattern while also allowing some subscribers to scale-up to handle received messages.

Apache Kafka #

Apache Kafka isn’t an implementation of a message broker. Instead, it’s a distributed streaming platform.

Unlike RabbitMQ, which is based on queues and exchanges, Kafka’s storage layer is implemented using a partitioned transaction log. Kafka also provides a Streams API to process streams in real time and a Connectors API for easy integration with various data sources; however, these are out of the scope of this piece.

Topics #

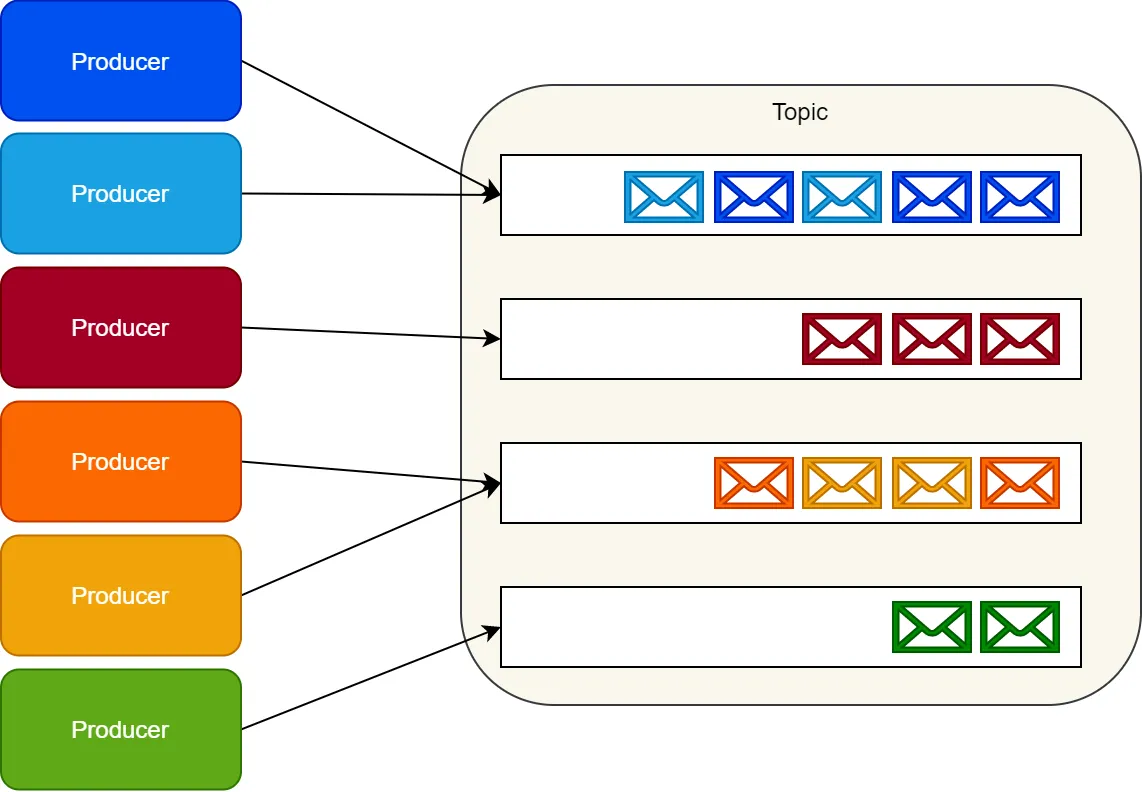

Kafka doesn’t implement the notion of a queue. Instead, Kafka stores collections of records in categories called topics.

For each topic, Kafka maintains a partitioned log of messages. Each partition is an ordered, immutable sequence of records, where messages are continually appended.

Kafka appends messages to these partitions as they arrive. By default, it uses a round-robin partitioner to spread messages uniformly across partitions.

Producers can modify this behavior to create logical streams of messages. For example, in a multitenant application, we might want to create logical message streams according to every message’s tenant ID. In an IoT scenario, we might want to have each producer’s identity map to a specific partition constantly. Making sure all messages from the same logical stream map to the same partition guarantees their delivery in order to consumers.

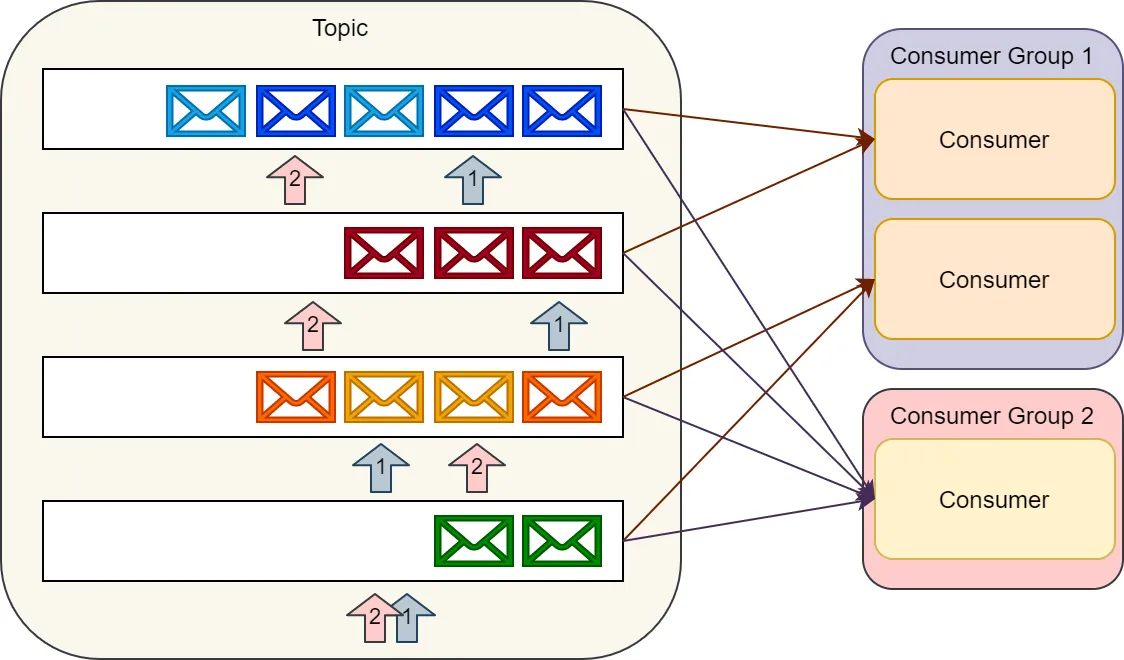

Consumers consume messages by maintaining an offset (or index) to these partitions and reading them sequentially.

A single consumer can consume multiple topics, and consumers can scale up to the number of partitions available.

As a result, when creating a topic, one should carefully consider the expected throughput of messaging on that topic. A group of consumers working together to consume a topic is called a consumer group. Kafka’s API typically handles the balancing of partition processing between consumers in a consumer group and the storing of consumers’ current partition offsets.

Implementing messaging patterns with Kafka #

Kafka’s implementation maps quite well to the pub/sub pattern.

A producer can send messages to a specific topic, and multiple consumer groups can consume the same message. Each consumer group can scale individually to handle the load. Since consumers maintain their partition offset, they can choose to have a durable subscription that maintains its offset across restarts or an ephemeral subscription, which throws the offset away and restarts from the latest record in each partition every time it starts up.

However, it’s a less-than-perfect fit for the message-queuing pattern. Of course, we could have a topic with just a single consumer group to emulate classic message queuing. Nevertheless, this has multiple drawbacks Part 2 of this piece discusses at length..

It’s important to note Kafka retains messages in partitions up to a preconfigured period, regardless of whether consumers consumed these messages. This retention means consumers are free to reread/replay past messages. Furthermore, developers can also use Kafka’s storage layer for implementing mechanisms such as event sourcing and audit logs.

Reference #

- https://www.rabbitmq.com/confirms.html

- https://www.rabbitmq.com/consumers.html#fetching

- https://www.rabbitmq.com/consumers.html#consuming

- https://www.rabbitmq.com/quorum-queues.html

- https://www.simplilearn.com/kafka-vs-rabbitmq-article

- https://www.interviewbit.com/blog/rabbitmq-vs-kafka/

- https://cloud.ibm.com/docs/EventStreams?topic=EventStreams-ES_understanding_reserved_disk_usage

- https://blog.ippon.tech/event-driven-architecture-getting-started-with-kafka-part-1/

- https://betterprogramming.pub/rabbitmq-vs-kafka-1ef22a041793

- https://betterprogramming.pub/rabbitmq-vs-kafka-1779b5b70c41